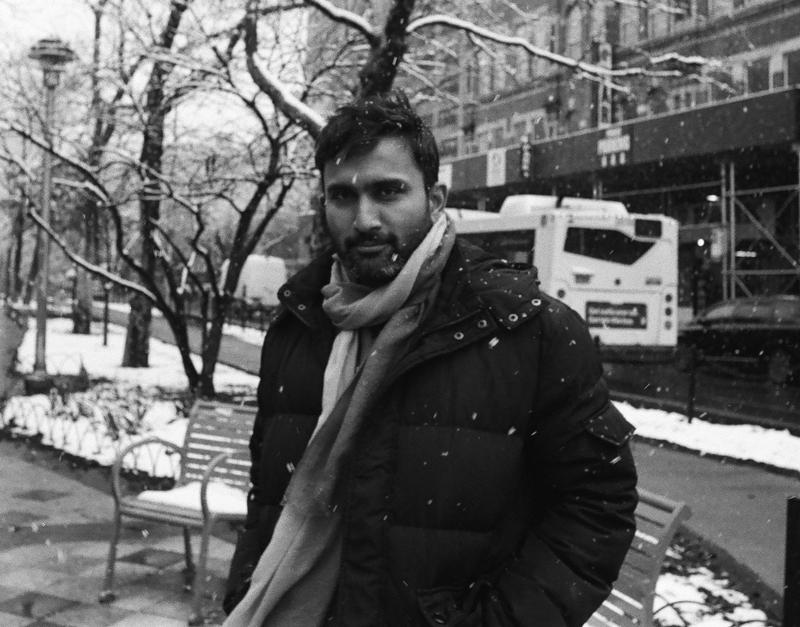

Photo by Inge Oosterhoff

Nigam Bhandari (ACC 2022) is a director, filmmaker, and co-founder of Cryptid Films, a Nepal-based film production company. He premiered three short films at the Busan International Film Festival in 2017, 2019, and 2021. In 2018, his short film Jaalegdi (2018) won Best Short in the K-Gen section at the Berlin International Film Festival. In 2019, his short film Song of Clouds became the first Nepali film ever to premier at Sundance. In the same year, he was invited by Berlinale to be part of their Talents Program, alongside other promising filmmakers worldwide. Bhandari’s ACC grant allowed him to complete his final year in the Graduate Film program at New York University (NYU) and create several short films.

We spoke with Bhandari in the last few months of the third and final year of his NYU program. Due to the impact and disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bhandari’s NYU cohort was provided an extension of an additional year by the school to take courses in person and utilize NYU’s many on-campus resources. We were particularly excited to hear about what he had learned and what he was looking forward to:

ACC: Which classes are you looking forward to taking in the extra year NYU has afforded you? Have any experiences stuck out to you so far in what you’ve been able to learn about cultural exchange?

NB: Well, it feels like all of them. For example, I could highlight the writing classes. A big problem in Nepal, when I was there and still right now, is in creating a screenplay. The screenplay is the most important thing in making a film, and I know really good, old storytellers and writers – but somehow the films that are being made are not of the same standard as the literature.

Photos by Victor Pigasse (left) and Rachel Turner (right)

I think this may partially be because we don't really have an industry in Nepal for cinema, and everybody is doing the best they can, but there needs to be a generation to learn something new and teach it to the next, and that didn't happen. Most film makers in Nepal learned their film or craft working in Bollywood or Indian films so [those styles and techniques] became the trend. Every Nepali film would take Bollywood formula – and the formula was almost always something like 5 songs and 4 action sequences. But because the Internet opened the world to us in the 2000s, all of the sudden we were watching things from all over the world saying, ‘Oh whoa, there's this entirely different thing possible’, but nobody had connections to understand how these things were made.

In the last 10 years, a lot has changed. Many of us have started going out to big festivals – I did not know there were film festivals 12 years ago. One of my colleagues has made several good films, and after he went to a festival he discovered, ‘Oh, so there's support internationally where people want to watch these films? And they will fund these films? Wow!’ I remember there was this whole revelation [from attending that film festival] when suddenly this colleague had a budget of $300,000 because he raised money from all over the world. The average Nepali film budget was around $60,000 or $70,000 and with that amount of money you can only do so much. With this internationally sourced money he made this wonderful film, and other filmmakers (including myself) did the same, getting into festivals and seeing the possibilities. People want to watch these stories. They want to help us make these films.

A second point would be on working with actors. Previously, I was working with non-actors all the time. So now I’ve gotten to work with actors and step into their shoes to understand how they think and that has been amazing for me – very refreshing and special.

Photo by Manya Glassman – Bhandari: “The NYU graduate film program is one of the last few film programs in the world where the students learn to shoot on actual film.”

Also in my case, being from Nepal, I didn't have an idea of how global business or industries worked. The way my classmates here think – even before film school, just through living here as their experience – if they had a product from England, they probably knew it was possible to then sell it in the US. It would be easy and normal for them, but not for us. I know family, cousins, and friends who are farmers back home, and then I walk around in Brooklyn in these grocery stores and see this food that is 50 times more expensive and I'm thinking, ‘Whoa. If they could get their products to New York, they could make a decent living.’ It's kind of similar when it comes to films, you know asking, ‘How does this industry work?’ or ‘How do we get things made?’ And on top of that, there's the obstacle of American films in Hollywood vs working in the setting of world cinema – the structures will probably be similar but not exactly the same market or system.

There's a class taught by Professor Peter Newman where we talk about film business, but in taking the course my classmates and I put forward that the content was very American, very Western. A lot of us are internationals, so he changed that class recently to make it an international class with international perspectives.

I think those three [writing, working with actors, and learning about global business] have been on my mind a lot because I feel like I've grown from them, and I talk about these things with my friends at home, so those three are important for me.

ACC: Since you’re the first Nepali-native to do this NYU Graduate Film program, and you have several other international classmates, what are you learning from them in terms of their culture and global perspectives?

Bhandari Celebrating Professor Carol Dysinger’s Oscar win in 2019 for Best Documentary Short Subject for her film “Learning to skateboard in a warzone (if you’re a girl)”

Bhandari Celebrating Professor Carol Dysinger’s Oscar win in 2019 for Best Documentary Short Subject for her film “Learning to skateboard in a warzone (if you’re a girl)”NB: There is something common among a lot of these students. I have classmates from India, China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, and some of them I’ve worked with before…I think there's something common among us that's putting us here – we share a culture in the way we speak, the way we think about using film or working on a script. I think there's an inevitability there, a culture we know that helps make us comfortable with one another.

There was an Indian student who wanted to make a film, and she went home to India to work with some local filmmakers, but it wasn’t working out. The language and culture are different [for production] because she wasn’t making a Bollywood movie. Then, she found that I was in Nepal, Kathmandu through NYU, and within the next week I'm flying on a plane to India and we're doing this film. It was fantastic.

Now, we're thinking up stories we wouldn't have even dared to make before. The film industry is kind of divided by borders, so at first there's a Bangladeshi filmmaker making Bangladeshi films, Pakistani filmmaker making Pakistani films. But because South Asia is so connected in terms of history through families and historical figures who moved around the world, you can build shared stories. If we work together to make those stories, it's not just India or Nepal or Bangladesh anymore, it’s something different. It’s also even better in terms of financing a film, because suddenly you have a market that's way bigger. Opportunities are opening and we are sharing stories with each other and sharing points of view.

ACC: Do you feel like you have brought some of your own knowledge of Nepali film and culture to the US, NYU, and the different people you are learning from/with?

Photo by Victor Pigasse – During Covid, Bhandari quarantined with 5 of his classmates in an Airbnb in Providence RI for two months and filmed their short films together.

NB: Most of the people I meet do not really know about Nepal…they are surprised to meet me, and when we start talking, they are kind of taken aback by how much I know about the West – it seems like they don't expect that. They have this image of Nepal as being really remote, but there's a whole generation now that's like me, doing insane things and inspiring people. And really, [Nepal has] been so small in terms of production and ambition, it feels like we haven't gone out and done things for the world because it's been so focused on Nepal. But now I feel like that change is happening. Things are opening up and this whole generation, who thinks big – not just for their village or town – is expanding their reach in the world. This kind of surprises me, but I love meeting Nepalese colleagues who are aiming for those big ideas. Although, at the same time there are barriers to entry. Our passport is one of the worst in the world, so even if somebody has the financial means to go out and see the world, that can prevent them.

ACC: What are you are most looking forward to after fully finishing your NYU program?

NB: In terms of school, I'm writing this short film that will be a complete project on its own. If the short film is successful, it would be used to raise funds and make a bigger film possible as well, so there are simultaneous projects going on. That short film will be done in Nepal in the Himalayas, 4,000 meters up in a place where foreigners were banned from entering until the 90s, and it still looks like a town from the village in the 13th or 14th century. I’ve realized that many people make films across the world, but not a lot of people I know have access and do projects quite like this. I'm trying to make cultural exchange happen through this project. I want to take some of my classmates and other NYU filmmakers – who I share creative culture with – to connect with filmmakers back home that I've been working with my whole life. I'm very excited to make this possible, to take them to Nepal and work there. It will be a short film, probably 15 minutes, but in terms of logistics it will be an international production and I'm very excited about that. Financially, the project will be very challenging. In terms of raising funds, we calculated the budget to be at least $25,000, which is a huge amount for a country like Nepal, but my friends and classmates here have been able to raise money like that for their films, so it seems possible, but just new territory for me.

Photo by Manya Glassman – Bhandari with professor Spike Lee, the Artistic Director of the NYU graduate film program, in his office.

Photo by Manya Glassman – Bhandari with professor Spike Lee, the Artistic Director of the NYU graduate film program, in his office.I'm also working on this feature story with a Nepali producer which has already been selected for the Busan International Film Festival’s Project Market Lab, so we will pitch there and hopefully that will happen in the next few years, right after I graduate.

Regarding New York, I came here, and the pandemic happened so I didn't get to experience this place a lot at first. But now I am trying to spend more time learning about culture and family here and it's really fun. I’m trying to spend more time in Jackson Heights to see the Nepalese and immigrant population there. I’m hoping to make a short film in New York, but it has been tough coming up with the story because I feel like I do not know this world a lot. So, I'll be spending this year and the next writing and preparing that short film to be shot in Nepal and searching for a story in New York – hopefully I can make a film here. If I can get actors or somebody from Nepal to come here and act, that would be amazing too because even though there a lot of Nepali speaking people here, it's difficult to find actors who speak the language. I'm also generally working with filmmakers in Nepal, writing small projects, developing things to make small films for the Nepali market, so that's fun too.

ACC: You’re doing several different projects and working with so many people while you’re completing this graduate program – what do you do to relax in New York City? How do you find rest while you are here?

NB: To me, being on a film set seems like a fun vacation! But also, I've had the opportunity to take some friends to Jackson Heights to some Nepali restaurants, introducing them to some Nepali foods. I used to go to museums too, but now I would prioritize American cultures a little more. The last time I was here my friends invited me over for Thanksgiving dinner, which was nice, so I want to learn how to cook American food and make a point of eating things my friends eat. I want to learn that because I know it's the tiny, little things that become special, it’s about food and about stories. The most fun is when some of us filmmakers and friends gather somewhere over drinks, and we start sharing stories and experiences – I think that tends to be the highlight of my week.

I'm also learning stories of how my friend (and roommate) grew up with his family in South Carolina surrounded by religion. It's foreign to me but listening to his stories of how those religious values and beliefs shaped his upbringing and his family is fascinating for me to learn about. I’m able to share things with him, so we find this common story and I think that's becoming my introduction to the US and cultural exchange. I'm listening to a lot of stories and learning about personal histories and that's really the highlight.

Follow Nigam Bhandari: Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | LinkedIn

ACC New York

ACC New York